There’s a new molecule of interest in the ongoing investigation into what causes heart disease and other chronic conditions: TMAO. But where does TMAO come from? Why is it bad for your heart? And how can you minimize it in your body? Find out how TMAO affects your health and whether you may need to make changes to your diet.

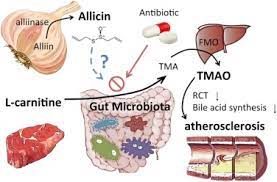

There’s a new molecule of interest in the ongoing investigation into what causes heart disease and other chronic conditions: TMAO. But where does TMAO come from? Why is it bad for your heart? And how can you minimize it in your body? Find out how TMAO affects your health and whether you may need to make changes to your diet.Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) is a metabolite that your body produces if you eat certain foods. Here’s how it works: when you consume foods rich in TMAO precursor compounds, the bacteria in your gut convert them into a molecule called trimethylamine (TMA). Your liver then grabs that TMA, does some fancy chemical stuff to it (apologies for that technical sidebar), and generates TMAO.

The dietary precursors to TMA formation, which include L-carnitine and choline, as well as betaine and lecithin, are found almost exclusively in foods of animal origin. Red meat like beef, pork, eggs, and lamb, as well as salt-water fish, lead to the highest concentrations of TMAO in our bodies. Liver, dairy products, and shellfish are also TMAO producers.

L-carnitine supplements can also increase TMAO levels in the body. One 2015 study found that when 31 patients on hemodialysis received L-carnitine supplements, it was changed to trimethylamine (TMA) by their intestinal microbiota, and then further metabolized to TMAO.

Why is TMAO bad for your health?

Researchers are discovering more and more associations between TMAO levels and the development of multiple inflammatory conditions. These include heart disease, type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, cancer, and liver disease.

How can you reduce TMAO levels in your body?

Minimizing foods that are very high in choline, L-carnitine, and other TMAO precursor compounds is the most effective way to reduce TMAO levels. And the easiest way to do that is to avoid the foods they come from — swapping animal-based foods for whole foods, plant-based ones.

The average TMAO in the study participants was over 10 μmol/L when they started the study, which put them in the highest risk category. Just one week later, a vegan diet had cut that number almost in half, to 5.7. Just like that, the participants were in the lowest risk category. Their TMAO levels remained fairly constant after eight weeks on the vegan diet. At week 12, however, following 28 days of rebound eating that included animal products, their TMAO levels had also rebounded, averaging a whopping 17.5 μmol/L.

For the complete article click here